week 1 (special relativity)

- in Newtonian physics, one cannot measure their own velocity with respect to some absolute reference frame, since interactions depend only on their interactants' velocities relative to each other.(ie. isotropic => invariant under rotation, homogeneous => invariant under translation, "velocitogeneous" => invariant under velocity-change)

- however, Maxwell's equations state the speed of light is constant.

- the idea that light is constant in a basis reference frame called the æther was called into questionby the

-

the Earth's movement within this basis frame would affect the distance the light travels.

say Earth is moving at \(v\) in the \(x\) axis, and you shine a ray moving at \(c\) 1m to and from a mirror in the \(x\) axis; it takes \(\frac{1m}{c-v}\) to get there, and \(\frac{1m}{c+v}\) to get back, so \(\frac2{c-\frac{v^2}c}\) time in total.

meanwhile, firing it perpendicular to \(x\) (from the Earth's frame) means the light travels (in the basis frame) with a hypotenuse speed of \(c\) but an \(x\)ward component of \(v\), so (in the Earth frame) moves with speed \(\sqrt{c^2-v^c}\).

since \(\frac{2m}{c-\frac{v^2}c}>\frac{2m}{\sqrt{c^2-v^2}}\) (for \(0\lt v\lt c\)), travelling with the Earth would be slower than perpendicular, which could be observed via phase-shift (but was not)

- there was an

æther drag hypothesis that the earth would be affecting the velocity of æther it moves through, like a shockwave - however Einstein observed that other parts of Maxwell's equations, like moving a magnet through a conductor, were velocitogeneous, so wanted an ætherless theory in which light can be too

- that is, every inertial reference frame observes the same laws of physics

- however, whereas Newton's physics is invariant under translation, rotation and

of inertial frame (multiplying spacetime positions \(\begin{pmatrix}\vec s\\t\end{pmatrix}\) by \(\begin{pmatrix}1&-\vec v\\0&1\end{pmatrix}\)), Einstein's special relativity would replace those with Lorentz boosts (multiplying by \(\begin{pmatrix}\cosh(\zeta)&-\sinh(\zeta)\\-\sinh(\zeta)&\cosh(\zeta)\end{pmatrix}\), where \(\zeta\) is the 'rapidity' of the boost) - this is for special relativity in 1+1D (in which case it is equivalent to multiplying the position vector by a split-complex 'unit number,' when considering time the reals and space the jmaginaries); now the full 3D case

- (in Planck units) if a frame \(F'\) is moving at speed \(\vec v\) relative to frame \(F\), the Lorentz factor (number of seconds perceived by an observer moving with \(F'\) for what one in \(F\) measures as 1 second) is \(\gamma=\frac1{\sqrt{1-v^2}}\); with \(\alpha=\frac{\gamma^2}{1+\gamma}\), transforming from \(F\) to \(F'\) is done by

- \[\begin{pmatrix}x'\\y'\\z'\\t'\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}1+\alpha v_x^2&\alpha v_xv_y&\alpha v_xv_z&-\gamma v_x\\\alpha v_xv_y&1+\alpha v_y^2&\alpha v_yv_z&-\gamma v_y\\\alpha v_xv_z&\alpha v_yv_z&1+\alpha v_z^2&-\gamma v_z\\-\gamma v_x&-\gamma v_y&-\gamma v_z&\gamma\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\\t\end{pmatrix}\]

- with \(u=\frac v{\Vert v\Vert}\) and \(\beta=\Vert v\Vert^2\alpha=\gamma-1\), this becomes

- \[\begin{pmatrix}x'\\y'\\z'\\t'\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}1+\beta u_x^2&\beta u_xu_y&\beta u_xu_z&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_x\\\beta u_xu_y&1+\beta u_y^2&\beta u_yu_z&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_y\\\beta u_xu_z&\beta u_yu_z&1+\beta u_z^2&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_z\\-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_x&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_y&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_z&\gamma\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\\t\end{pmatrix}\]

- the determinant of the \(3\times3\) space-to-space submatrix is again \(1+\beta(u_x^2+u_y^2+u_z^2=1)=\gamma\), and of the total is \(1\) (ie. the compression of both time and space is counteracted by the amount they add to each other).

- we get out the rapidity formulation by using \(\gamma=\cosh(\zeta),\gamma\Vert v\Vert=\sinh(\zeta)\); the benefit of this is that composing two boosts in the same direction adds their hyperbolic angles.

- note that in the 1+1D case, the eigenvalues are diagonal (and 'lightlike'); if \(F'\) is moving in positive \(x\) from \(F\)'s perspective with rapidity \(\zeta\), then within \(F'\), light travelling in positive \(x\) is \(e^\zeta\) times denser in spacetime, and in negative \(x\) is \(e^\zeta\) times sparser (the two eigenvectors being lightlike); in the \(n+1\)D case, there are two perpendicular eigenvectors with distinct eigenvalues (compression and dilation), and the rest of the dimensions in a trivial eigenspace with eigenvalue \(1\)

- as one 'zooms in' and \(\Vert v\Vert\rightarrow0\), Lorentz transformations approach Galilean transformations, and the perception of special relativity approaches classical physics

- on p. 27 of the slide, the Michelson-Morley experiment is again described, except in this case (since measurement in the same earthly reference frame would give a constant speed) as measured by an observer in an "æther frame" as the Earth moves past at speed \(v\).

-

so, in the Earth's reference frame, the light moves from \(\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\t\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}0\\0\\0\end{pmatrix}\) to \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1\end{pmatrix}\) (we need not distinguish \(y\) and \(z\) here)

\[\begin{pmatrix}x'\\y'\\t'\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}1+\beta u_x^2&\beta u_xu_y&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_x\\\beta u_xu_y&1+\beta u_y^2&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_y\\-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_x&-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_y&\gamma\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}1-\gamma\Vert v\Vert u_x+\beta u_x^2\\u_y(\beta u_x-\gamma\Vert v\Vert)\\\gamma(1-\Vert v\Vert u_x)\end{pmatrix}\]

- if the observer moves perpendicular to the light (\(u_x=0,u_y=1\)), it will observe the light travelling in \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\-\gamma\Vert v\Vert\\\gamma\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}1\\-\sinh(\zeta)\\\cosh(\zeta)\end{pmatrix}\)

- if the observer moves parallel (\(u_x=\pm1,u_y=0\)), it will observe \(\begin{pmatrix}1\mp\gamma\Vert v\Vert+\beta\\0\\\gamma(1\mp\Vert v\Vert)\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}\cosh(\zeta)\mp\sinh(\zeta)\\0\\\cosh(\zeta)\mp\sinh(\zeta)\Vert\end{pmatrix}\), as aforementioned

so, we have the table of observed times

parallel perpendicular classical \(\frac{2m}{1-v^2}\) \(\frac{2m}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}\) relativistic \(\frac{2m}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}\) \(\frac{2m}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}\) the equivalence follows from velocitogeneity; the time taken by the light to do the closed loop is constant from the reference frame of the emitter/detector in \(F\) irrespective of the light's direction, and remains so when time-dilated by a Lorentz boost.

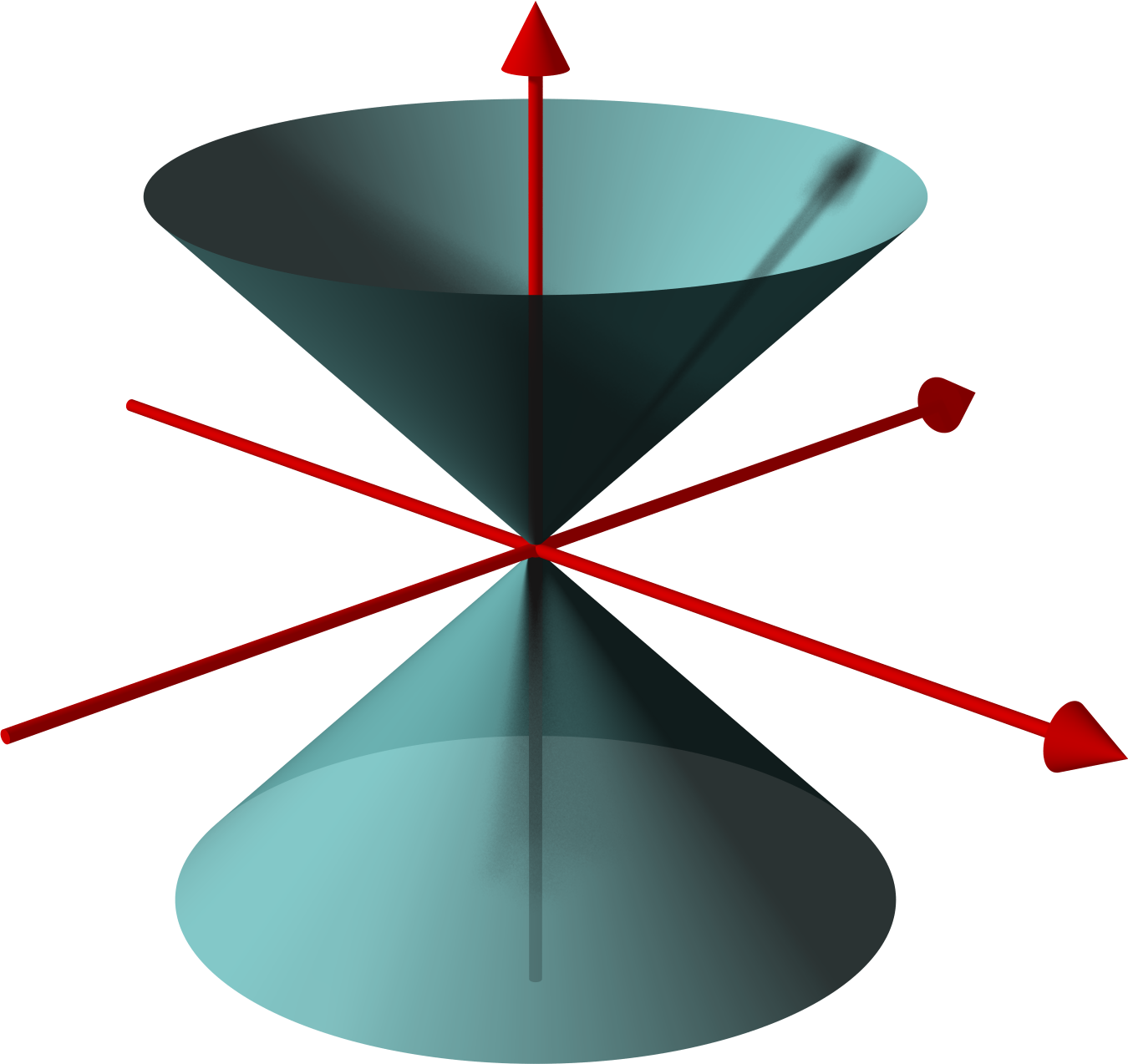

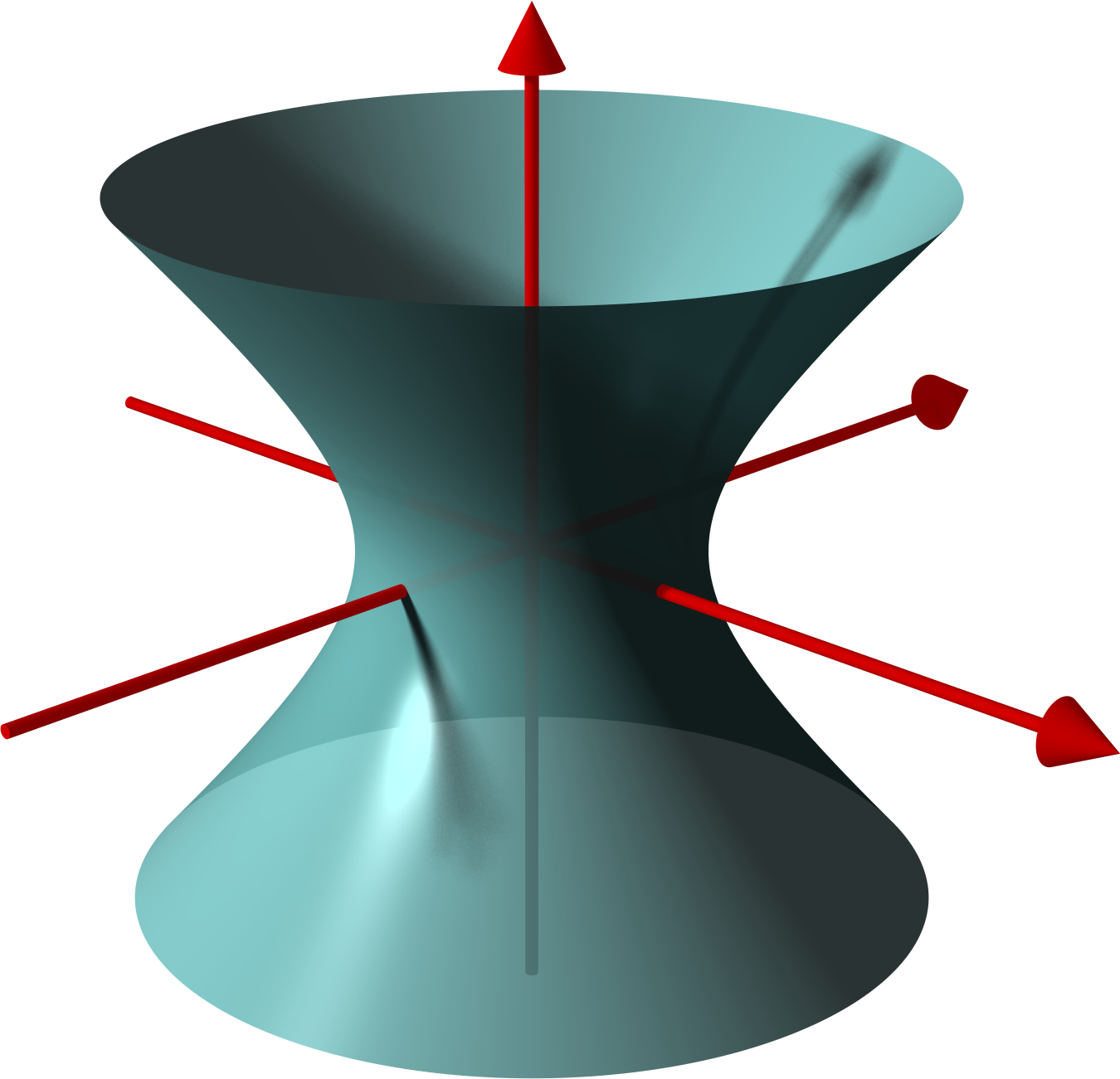

- similarly to how the orbits under trigonometric rotations are circles of constant \(\mathrm{Re}^2+\mathrm{Im}^2\), the orbits under hyperbolic ones are hyperbolae of constant \(\mathrm{Re}^2-\mathrm{Jm}^2\); since a 3+1D hyperbolic rotation has time form \(\mathrm{Re}\), one space vector form \(\mathrm{Jm}\), and the spatial plane perpendicular to both left invariant, the orbits under the union of all rotations are hyperboloids.

each spacetime hyperboloid with \(s=\mathrm{sgn}(t)\sqrt{t^2-x^2-y^2-z^2}\) has the physical interpretation as being the set of points that the origin (travelling with any constant velocity) will take a constant amount of time (in its own inertial reference frame) to reach; if point \(B\) in spacetime has a given value of \(s\) from \(A\)'s reference frame, \(A\) will have a value of \(-s\) from \(B\)'s.

two sheets cone one sheet

note that as wll as hyperboloids inside the cone (of points a constant perceptual time away from you irrespective of trajectory) and the cone (of points you could reach at lightspeed), there are also hyperboloids outsiede the cone (of points you are accursed never to access or vice versa)

- we can also adjust the aforementioned relativistic Michelson-Morley experiment; say instead an emitter in frame \(F\) fires off two photons \(\Delta t\) time apart, which are received by another in frame \(F'\); Newtonianly, their distance in space from the observer's reference frame is \(\Delta x'=(1-v\cos(\theta))\Delta t\) (with \(\theta\) the angle between the observer's direction to emitter and direction of motion), and Einsteinianly, their distance in \(F'\) time is thus \(\Delta t'=\frac{1-v\cos(\theta)}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}\Delta t\). (In the case that the observer is moving directly towards the emitter, this is \frac{\sqrt{1-v}}{\sqrt{1+v}}, and if moving away, \frac{\sqrt{1+v}}{\sqrt{1-v}}.)